“My research, work, and scholarship are about how African Americans create community—how they use institutions to get autonomy and self-definition and self-manifestation to create spaces of freedom.”

—Dr. Melissa N. Stuckey, Assistant Professor of History and Social Sciences at Elizabeth City State University

By Amy Beth Wright

Dr. Melissa N. Stuckey’s work as a professor extends far beyond the classroom. At Elizabeth City State University, Dr. Stuckey is part of a team working to restore a Rosenwald practice school on campus that marked its centennial last year, having opened to students in 1922. As part of her vision to remap segregation-era African American businesses in Elizabeth City onto Google Earth, Dr. Stuckey’s students acquire primary research skills, understanding, “the kind of research that allows scholars to be scholars.” Here, Dr. Stuckey shares why both projects are integral to understanding how African American activism, migration, movement, and community have created, and continue to create, “spaces of freedom” in the United States.

How did your scholarly focus on early 20th century activism first come about?

I got my Ph.D. in 2009. My dissertation is about the all-Black town of Boley, Oklahoma. This incorporated town was in Creek Nation territory, so outside of the United States proper. That work explores how ideas of black freedom were impacted by statehood; Oklahoma became a state in 1903 and immediately enacted laws that discriminated against African Americans. The dissertation and future book (All Men Up: Seeking Freedom in the All-Black Town of Boley, Oklahoma) are about how African Americans envisioned freedom and then had to protect it, fighting against legalized forms of segregation even within the confines of an all-Black town.

The larger written work will include Black attempts at freedom here, through the Great Dismal Swamp and with figures like waterman Moses Grandy, an enslaved person in this area in the early 1800s. It will move all the way through 2021, when communities within Elizabeth City came together to protest the shooting and killing of an Elizabeth City resident by county sheriffs. At both moments and in between, African American people have marched along or through the streets of Elizabeth City in patterns through certain neighborhoods and roads and streets, generation after generation after generation, in search of freedom.

Were you drawn in this direction prior to starting your Ph.D.

Absolutely. My family is originally from South Carolina. Our origin story is at two roads within a predominantly black township called Rembert. The paved road is where my great-grandparents lived, in a small home. The dirt road was built through a swath of land they purchased so their children would each have an inheritance of a piece of the land. My grandmother attended a Rosenwald school in South Carolina. She graduated and married my grandfather during World War II. They moved from this rural South Carolina space to Washington, D.C., and then to New Jersey, which is where I’m from originally. This idea of migration carries through my interest in African American stories as a community and a movement.

My first visit to South Carolina was when I was five. As a little girl growing up in very urban New Jersey, to go to the country for the first time and be in a place that had very few city lights and lots of trees and night sounds that you get in swampy forest areas and to be amongst country folk who spoke very differently to my ears than I’ve ever heard anyone ever speak…The sights and sounds and smells were incredibly different for me. I could see how happy my grandmother was there. She had this look of contentment, amongst her sisters and her brothers, and her children and grandchildren. It was a really important moment for me. I can now look back and understand what’s really important about that place in South Carolina: the community, the migration, the connectivity, the autonomy, whether they’re micro, like a neighborhood in rural South Carolina, or macro, in terms of a black town in Oklahoma.

What drew you to Elizabeth City as an educator?

I’m very interested in thinking about what Black freedom would look like from the lens of a historically black institution and within a historically black neighborhood. We can’t look at it as just a college, although it’s certainly an important educational institution for the region. It’s also an important cultural institution, an anchor for the Black community within the 21-county region that it serves and beyond.

For example, ECSU started its life in 1891 as Elizabeth City State Colored Normal School; normal schools were designed to educate and train teachers. This dedicated space is a big deal, and multi-layered—it was an elementary school, a training school, and a connector to the larger northeastern North Carolina community, because those graduating students became the region’s teachers. Northeastern North Carolina had 235 Rosenwald schools, a good chunk of the over 800 Rosenwald schools in the state. The normal school’s impact can be counted through the number of teachers in Rosenwald schools and other primary and high schools across the region.

How is the rehabilitation progressing?

I arrived in the fall of 2017, and some important momentum-building steps, like getting studies of the buildings done, happened then. I then applied, along with a team of folks here, for a few major grants. We were awarded a National Park Service grant of just shy of $500,000 to begin the rehabilitation process in 2019, along with a planning grant from the Institute of Museum and Library Services. I’ve applied for several more grants to continue the work through the rehabilitation and for the research, design, and construction of exhibits that impart northeastern North Carolina’s Rosenwald school histor

In the future, we will host workshops for Rosenwald alumni on writing grants to rehabilitate Rosenwald schools and how to collect archival material and have that material digitized.

Will you engage the community around this project?

I’m giving many talks. In February we screened the documentary Unlocking the Doors of Opportunity: The Rosenwald Schools of North Carolina, produced by Longleaf Productions. The filmmakers Tom Lassiter and Jere Snyder shared more during a Q&A after the film.

What was education like in Elizabeth City prior to the Rosenwald schools’ program?

There were public schools, but they were overcrowded and run down. There was a real need for better public educational facilities for children, black and white, in Elizabeth City.

The challenge African Americans faced is that the level of funding invested into public schools was starkly uneven and unfair within the segregated school system. When new schools were built for white children and books were purchased for them, black kids got the leftovers, remainders from the previous schools. The Rosenwald School program, among others, served as intervention and gave state’s incentives to invest more money into public education for African Americans.

One of the most interesting things is that the Rosenwald school program was a matching program. It required African American communities to give cash, labor, and (or) land to the creation of the school building, and county school boards to do the same. What is poignant about this is that the African American community was already paying taxes that went to public school funds in their states. But they were asked to pay even more to have adequate facilities for their own children. Those contributions didn’t end with the creation of the school building. They were paying for books, school buses, electricity.

Was there ever a correction to this imbalance—reimbursement, or tax credits?

No; Rosenwald schools existed within the larger ecosystem of unequal treatment African Americans experienced in the United States

Was slavery predominant in Elizabeth City?

Slavery was an important part of the economy. Was it a place of huge plantations? No. That’s one of the bigger misconceptions about slavery though. It was more common for it to be the way it was here, a mixed economy, in the city and on county farms—enslaved people would be required to do all kinds of work in different kinds of circumstances. There were enslaved men who captained boats and lived semi-independent lives, where they paid a certain amount of money to their slave owner based on their trade.

Is your project on mapping Elizabeth City separate from your scholarly work, or is it all sort of connected?

That’s one of several projects I’m involved in simultaneously. I worked a lot on it last year with my students. Last year, we identified 75 African American owned businesses in Elizabeth City between 1940 and 1943. Through presenting that work to the public, we are beginning conversations with folks who remember those businesses, because either they were operated by family members or because they were patrons of them. There were supermarkets, restaurants, dance halls, ice cream shops, an African American owned bank, doctors, dentists, hairdressers, barbers. It was a really vibrant community. We are mapping that back onto a modern landscape that has many empty lots and that has endured street name and address changes and configurations. My students are doing the investigative research. They’re finding passion for better understanding the present by studying the past.

A Few Historical Markers to Visit in Elizabeth City

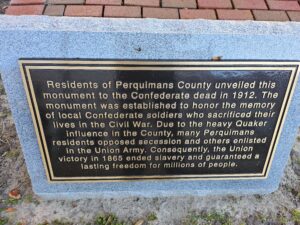

Markers related to African American history and the Civil War, in addition to the Civil Rights movement, are within a couple hundred feet of each other in downtown Elizabeth City.

A new historic marker on Main Street honors students who participated in a 1960 sit-in to desegregate a lunch counter at a thrift store called the W.T. Grant Store.

A marker on the National Votes for Women Trail honors 1901 ECSU (the Elizabeth City State Normal School at the time) graduate Annie E. Jones, who organized Black women through the National Association of Colored Women’s Clubs after the passage of the 19th Amendment. Jones prepared women to pass the state literacy test that was used to fail and deny African Americans voting rights.

A historic marker on Water Street commemorates Wild’s Raid, when African-American troops conducted reconnaissance missions during the Civil War.

Elizabeth City State University’s on-campus historic district is called the Elizabeth City State Teachers College Historic District, and is home to the Rosenwald School, the principal’s house, and other historic buildings. A highlight is a beautifully restored auditorium.