By Amy Beth Wright

Johnica Rivers is an eighth-generation Texan, a journalist, a writer, and a curator. In 2017, after seven years as a travel writer, a project about the revolutionary Black artist, feminist, and activist Elizabeth Catlett, led her to the Center for Documentary Studies at Duke University. “I was looking for a way to deepen how I cover travel narratives. I thought perhaps seeing things through the documentary studies lens would provide the depth I was searching for,” recalls Rivers. Classes with Michelle Lanier, who was the founding executive director of the African American Heritage Commission (part of the North Carolina Department of Natural and Cultural Resources) and the director of The Harriet Jacobs Project, influenced the pathway of Rivers’ life and work.

Johnica Rivers is an eighth-generation Texan, a journalist, a writer, and a curator. In 2017, after seven years as a travel writer, a project about the revolutionary Black artist, feminist, and activist Elizabeth Catlett, led her to the Center for Documentary Studies at Duke University. “I was looking for a way to deepen how I cover travel narratives. I thought perhaps seeing things through the documentary studies lens would provide the depth I was searching for,” recalls Rivers. Classes with Michelle Lanier, who was the founding executive director of the African American Heritage Commission (part of the North Carolina Department of Natural and Cultural Resources) and the director of The Harriet Jacobs Project, influenced the pathway of Rivers’ life and work.

Harriet Jacobs was born into slavery in 1813, in Edenton, North Carolina. Margaret Horniblow, “a relatively kind mistress,” writes William L. Andrews, taught her to read and sew. When Jacobs was eleven, Horniblow passed away, and Jacobs was bequeathed to Horniblow’s three-year-old niece, Mary Matilda Norcom; the child’s father, Daniel Norcom, became Jacobs sexual terrorizer. Isolated in the household, describes Andrews, Jacobs bore two children with a white attorney named Samuel Tredwell Sawyer. Later, Jacobs hid for seven years in a crawl space above a storeroom in her grandmother’s house, expecting Sawyer would purchase and emancipate their children. He did purchase them, but failed to do the latter, sending their daughter Louisa to Brooklyn to work as a servant. In 1842, Jacobs sailed north to Philadelphia, ultimately resettling both of her children with her in Boston. She published anonymous letters about her experiences while enslaved in the New York Tribune before publishing Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl under the pseudonym of Linda Brent in 1861, becoming, writes Andrews, “the first woman to author a fugitive slave narrative in the United States.” In her later years, she was a relief worker on behalf of former slaves and ran a school in Alexandria, Virginia and a boarding house in Washington, D.C.

“She was peripatetic, making many footballs once she left Edenton. But she also returned to Edenton after she was free,” explains Rivers.

Rivers completed the documentary studies certificate program at Duke. When Lanier became the director of the North Carolina Division of State Historic Sites (also within the NC Department of Natural and Cultural Resources) she hired Rivers as curator-at-large of The Harriet Jacobs Project. Rivers explains, “We are both drawn to inter- and transdisciplinary approaches, the ways the visual, performing, and literary arts connect to histories.” Lanier has also produced the Edenton launch of scholar Jean Fagan Yellin’s The Harriet Jacobs’ Family Papers and spearheaded placement of the Harriet Jacobs Highway marker on Broad Street in Edenton.

Rivers completed the documentary studies certificate program at Duke. When Lanier became the director of the North Carolina Division of State Historic Sites (also within the NC Department of Natural and Cultural Resources) she hired Rivers as curator-at-large of The Harriet Jacobs Project. Rivers explains, “We are both drawn to inter- and transdisciplinary approaches, the ways the visual, performing, and literary arts connect to histories.” Lanier has also produced the Edenton launch of scholar Jean Fagan Yellin’s The Harriet Jacobs’ Family Papers and spearheaded placement of the Harriet Jacobs Highway marker on Broad Street in Edenton.

Lanier conceived of activating the 1767 Chowan County Courthouse, a national landmark and state historic site that’s part of Historic Edenton, with visual art. Rivers considered what “a quiet punch, a really impactful way a space can still breathe” might be. Texas artist Letitia Huckaby, a photojournalist and documentary photographer, prints on fabrics that have roots, or historical ties, to the southern United States, and seemed an instinctive fit for the project based on her interest in documenting women’s experiences, and their migrations, or footfalls, through space.

Harriet Jacobs doesn’t have direct descendants in her line, (neither her son or daughter had children). Rivers and Huckaby partnered with the women of the Fannie A. Parker Women’s Club; Huckaby photographed the women and printed their portraits on cotton flags that were installed in the courthouse windows, the women in silhouette in the window frame, backlit as day gives way to dusk and evening. The exhibition is called Memorable Proof, and debuted as part of three-day immersion called A Sojourn for Harriet Jacobs in March of 2024. Says Huckaby, “I hope that the work will make Black people feel that when they come inside, or even if they see it from the outside if it gets the glow I hope it’ll have at night—that it’ll become this monument and marker of the greatness of Black people, not just a place where we were bought and sold or convicted and put in prison.”

Memorable Proof was also installed at the Love House on the UNC Chapel Hill campus, which houses the Center for the Study of the American South, during the fall of 2024. Lanier, Rivers, and Alexis Pauline Gumbs edited the summer 2024 volume of Southern Cultures, produced by the center, a volume called Sojourning that explores “sojourning as a creative and intellectual act,” explains Rivers.

Lanier and Rivers noted that while many artists, writers and scholars have studied and examined Jacobs’ life, few have been to Edenton, or to North Carolina. “There was a disconnect between Jacobs’ legacy and the land that held her origins,” says Rivers.

Lanier and Rivers noted that while many artists, writers and scholars have studied and examined Jacobs’ life, few have been to Edenton, or to North Carolina. “There was a disconnect between Jacobs’ legacy and the land that held her origins,” says Rivers.

A Sojourn for Harriet Jacobs brought seventy black women from all over the United States—scholars, writers, MacArthur geniuses, emerging artists and poets—to Edenton for a three-day immersion in Edenton’s waterways, sites, streets, and neighborhoods, and to bear witness to the first exhibition of Memorable Proof. Rivers likens the sojourn to taking a travel essay off the page to become a social sculpture, the women traveling to and processing through Edenton becoming part of the art.

In Burnaway magazine, attendee Niara Simone Hightower describes, “We would move […] as a dawning collective, gathered across generations to witness the enduring life of Jacobs by dwelling in the ‘land that saw it all,’ to therefore realize our own possibilities.”

*

When Rivers read Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl as an undergraduate, she noticed Jacobs contemporary, compelling writing style. Now, she is compelled by the “strategic” way she claimed her freedom and her life, an example for women today.

“Voluntarily enclosing herself in the garret space for seven years to get away from her abuser, a choice she could make as a counter to choices that were being made for her— taking autonomy into her own hands—that’s extremely compelling to me. The dedication and discipline to say, ‘I refuse to do that, so I’m going to choose to do this instead.’ And the many choices she made once she’s outside the garret as well, putting her gifts to use in many places, are inspiring. Harriet also had a place to hide because her grandmother, Molly Horniblow, orchestrated her own freedom. This is a lineage of women who were strategic in taking their lives back. That sits with me every day. Because if they could do it in those conditions, whatever conditions I may find myself in, I too, can make choices and be strategic. I want to inspire other Black women to make choices that allow them to write their own stories. Through this work, I make the choice to place myself in the lineage of Harriet Jacobs and to look for the best mediums to tell the stories of black women and cultural production—connecting the arts, literary production, and place,” says Rivers.

“Voluntarily enclosing herself in the garret space for seven years to get away from her abuser, a choice she could make as a counter to choices that were being made for her— taking autonomy into her own hands—that’s extremely compelling to me. The dedication and discipline to say, ‘I refuse to do that, so I’m going to choose to do this instead.’ And the many choices she made once she’s outside the garret as well, putting her gifts to use in many places, are inspiring. Harriet also had a place to hide because her grandmother, Molly Horniblow, orchestrated her own freedom. This is a lineage of women who were strategic in taking their lives back. That sits with me every day. Because if they could do it in those conditions, whatever conditions I may find myself in, I too, can make choices and be strategic. I want to inspire other Black women to make choices that allow them to write their own stories. Through this work, I make the choice to place myself in the lineage of Harriet Jacobs and to look for the best mediums to tell the stories of black women and cultural production—connecting the arts, literary production, and place,” says Rivers.

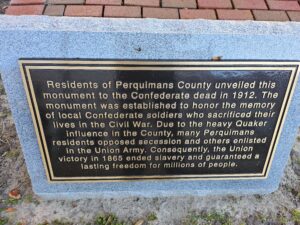

The sojourn was important because, says Rivers, “I want people to view land as source material. It’s not enough to read the book. It’s not enough to go into the archive. You need to go to the place. It’s difficult to understand the tight proximity, a ten-block radius, of everything that happens in Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl. There’s the level of danger, skill, and secrecy, and the respect that people had to have for Harriet’s grandmother, for her to hide where her abuser literally walked directly by the house to get to his office. You can’t understand that until you’re in Edenton. It gives you an embodied understanding of history, of a story, and it brings you into a contemporary moment. There are black people still in Edenton, and Edenton just took down a Confederate statue earlier this year. The people that are currently there also have stories that need to be told, that need to be advocated for, that need to be amplified. I think that’s the power of Memorable Proof. We honored Harriet Jacobs, but we also brought to the forefront the black women right now who are doing the work in Edenton.”

***

Memorable Proof will become part of a permanent collection within the North Carolina Division of State Historic Sites. Rivers is also working on two new commissions that respond to Jacobs’ story and Historic Edenton, and plans to extend the framework of arts activation to the Charlotte Hawkins Brown Museum in Greensboro, originally the site of Black boarding school called the Alice Freeman Palmer Memorial Institute. In 2024, North Carolina Historic Sites’ also brought artist Maya Freelon to Historic Stagville, the largest plantation in North Carolina. Freelon activated both the master’s house and the barn with tissue paper quilts alongside a motion-activated soundscape conceptualized and developed by Dr. Allie Martin of the Black Sound Lab at Dartmouth College.

References

Andrews, William L. “Harriet A. Jacobs (Harriet Ann) 1813-1897.” Documenting the American South. https://docsouth.unc.edu/fpn/jacobs/bio.html.