The Pea Island Preservation Society, Inc. marked the 125th Anniversary of the E.S. Newman shipwreck and rescue with a Governor’s proclamation and a reunion of descendants in October 2021.

By Amy Beth Wright

Dwight Meekins and Daniel Gardiner have met many times before; one particularly poignant occasion was in 1996, when the U.S. Coast Guard posthumously awarded their grandfathers and all of the Pea Island Lifesaving Station service members a Gold Lifesaving Medal, 100 years after their duty. Meekins and Gardiner recently reunited again on October 9, 2021 to mark the 125th anniversary of the daring rescue of the E.S. Newman shipwreck and rescue, along with many other descendants of the station’s crew and the Newman’s passengers. The event, hosted by the Pea Island Preservation Society, Inc (PIPSI), celebrates and preserves the story of the first U.S. Lifesaving Station manned by an all Black crew, which received little recognition in its time.

In the late 19th century, 30 U.S. Lifesaving Stations along the Virginia and Carolina coasts, particularly along Cape Hatteras, were critical during hurricane season. Shallow sandbars, or shifting shoals, placed many ships in distress. On October 11, 1896, Dwight Meekins’ grandfather, Theodore Meekins, spotted a distress flare lit by the captain of the E.S. Newman, Sylvester Gardiner (Daniel Gardiner’s grandfather), on board with his wife, his three-year-old son, and six crewmembers. The station’s commander (or Keeper) Richard Etheridge had two of his crewmembers tie themselves together with rope and swim out to the ship while the rest held the line. As darkness fell, moonlight and fires on shore provided the only light for the rescue of all nine passengers from a storm-tossed ocean. By 1:00 a.m., all were safe on shore. The crew received no formal commendation or medals at the time; the morning after the storm, Captain Gardiner gave Surfman Meekins the ship’s signboard, recovered on shore.

Richard Etheridge, explains retired National Park Service historian and PIPSI’s President Darrell Collins, was born into slavery, and believed to be the son of his owner John B. Etheridge, a prominent landowner and commercial fisherman. Working alongside John B. Etheridge, Richard became an expert waterman, who later served in the Union Army. As keeper of the Pea Island Lifesaving Station, he ultimately achieved, explains Darrell Collins, “a kind of purpose in life and equality that a lot of African Americans, at that time in history, wouldn’t experience within their lifetime.”

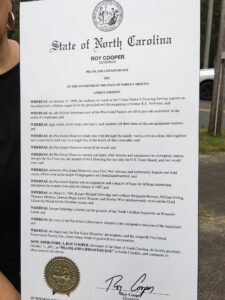

At the recent commemoration, Dwight Meekins and Daniel Gardiner placed a wreath on Etheridge’s gravesite at the North Carolina Aquarium, and PIPSI’s Director, Joan Collins, read a proclamation from Governor Roy Cooper aloud, naming October 11, 2021 as Pea Island Lifesavers Day. In the 1990s, retired U.S. Coast Guard Rear Admiral Stephen Rochon initiated a petition for a posthumous medal, and rejoined PIPSI to offer remarks at the October commemoration. His efforts in the 1990s were in concert with a letter-writing campaign initiated by a 14-year-old student who, upon realizing that other stations had received medals for rescues at that time, reached out to Senator Jesse Helms, who acted in support of the medal process. A documentary called Rescuemen also tells the story of the Pea Island lifesaving crew, and so does the book Fire on the Beach: Recovering the Lost Story of Richard Etheridge and the Pea Island Lifesavers, authored in 2000 by David Wright and David Zoby.

At the recent commemoration, Dwight Meekins and Daniel Gardiner placed a wreath on Etheridge’s gravesite at the North Carolina Aquarium, and PIPSI’s Director, Joan Collins, read a proclamation from Governor Roy Cooper aloud, naming October 11, 2021 as Pea Island Lifesavers Day. In the 1990s, retired U.S. Coast Guard Rear Admiral Stephen Rochon initiated a petition for a posthumous medal, and rejoined PIPSI to offer remarks at the October commemoration. His efforts in the 1990s were in concert with a letter-writing campaign initiated by a 14-year-old student who, upon realizing that other stations had received medals for rescues at that time, reached out to Senator Jesse Helms, who acted in support of the medal process. A documentary called Rescuemen also tells the story of the Pea Island lifesaving crew, and so does the book Fire on the Beach: Recovering the Lost Story of Richard Etheridge and the Pea Island Lifesavers, authored in 2000 by David Wright and David Zoby.

Darrell Collins and Joan Collins’ great-grandfather, Joseph Hall Berry, served under Etheridge, and their great-great uncle, W. Dorman Pugh, was one of the crewmembers that rescued the E.S. Newman. The last keeper of the station was also a great uncle, Maxie Berry, Sr., and Joan Collins father, Herbert M. Collins, who was the last surfman to serve at the station and helped to decommission it in March 1947. The station, formed during the Jim Crow-era of Reconstruction, earned a reputation as one of the best-kept stations on the coast. Etheridge, who recruited the all Black crew, died in May 1900, reportedly from malaria.

“Etheridge really opened the door of opportunity for so many Black men from this area to serve in the United States Lifesaving Service,” explains Darrell Collins. He compares the Pea Island Lifesaving Station to the Tuskegee Airmen, who were “organized and commanded by people of their own race, with all the infrastructure done by African-Americans. These men likely would have never had that opportunity to serve, had it not been for the reputation the station achieved over the years,” explains Darrell Collins.

Dwight Meekins served eight years in the Navy before deciding he belonged in the Coast Guard, a poetic continuation of his grandfather’s story. As part of a search and rescue unit, he was privy to or part of 137 rescues in his first year. Though Theodore Meekins passed well before his grandson was born, Dwight Meekins’ father Nicholas, who served in the Coast Guard during WWII, remembers his grandfather training in semaphore (sending message via flags), rowing, swimming, diving. Dwight Meekins recalls hearing about a drill Keeper Etheridge had his crew practice. “He’d roll out to 30-40 feet of water and throw five, ten, or fifteen pound weights in and his crew had to swim down and come back up with the weights.” Meekins says that on a scale of one to ten, the Newman rescue was a ten, although the Pea Island Lifesavers, “They had a whole lot of 7’s and 8’s. Its what the Lifesaving Service was set up for, and it’s what they did. In the Coast Guard, they used to say, ‘You have to go out, but you don’t have to come back.’ If somebody is in trouble, you are duty-bound to go help them, even at the peril of your own life.”

In his remarks, Meekins described Etheridge as “the epitome of a great leader, loved and respected by his men and other life savers and of course revered by those he rescued.” He noted that more than 600 people were rescued by Pea Island Lifesavers in the station’s 67 years, and closed with a reading of the poem “Invictus,” by William Ernest Henley.

PIPSI is now the “keeper” of Etheridge’s story and legacy, and imparting it to the next generation is top priority. Darrell and Joan Collins have developed an education program called “Freedmen, Surfman, Heroes” for the North Carolina Aquarium and for all fourth grade classes in Dare County. PIPSI is also piloting a virtual program for third grade students and, supported by a grant from the Z. Smith Reynolds Foundation, producing a documentary film that encompasses the station’s 67 years, beyond the famous Newman shipwreck. “There is much more to tell, and if we want to reach youth, we have to reach the adults,” says Joan Collins. To visit the Cookhouse Museum, volunteer, donate, or learn more about PIPSI’s educational programming, visit The Pea Island Preservation Society’s website.

The 125th Anniversary of the Newman Rescue included remarks from descendants Dwight Meekins, Frank Hester (great-nephew of Surfman Dorman Pugh), and Daniel Gardiner. Other speakers include Carl Smith, Chicamacomico Historical Association Board Member, Commander Matthew Baer U.S. Coast Guard North Carolina sector, PIPS board member Coqueta Brooks, and David Wright Falade. An interpretation of the wreck report was read by Jason Berry and Zay Williams, and Commander Baer facilitated a Gold Medal reenactment with community children, some of whom are also descendants. Joan Collins addressed the mission of the Pea Island Preservation Society and Retired Rear Admiral Stephen Rochon offered closing remarks. The event was in part sponsored by the Outer Banks Visitors Bureau, and intern Francesca Fradianni from the North Carolina Coastal Studies Institute contributed a poster design.

The all Black crew at the Pea Island Lifesaving Station was comprised of Richard Etheridge, Benjamin Bowser, William Irving, W. Dorman Pugh, Theodore Meekins, Lewis Wescott, and Stanley Wise.

Amy Beth Wright is a travel writer focusing on public lands, art, architecture, food, wine, history, and culture. She also writes autobiographical essays and teaches writing at Purchase College (State University of New York at Purchase). Read more of her work at amybethwrites.com.